BUTOH

If you prefer to read a handy summary about this topic, go to our butoh section in the contemporary dance history page. The following is an expanded version of it.

Butoh (舞踏) is the name given to a variety of performance practices that emerged around the middle of the XXth century in Japan.

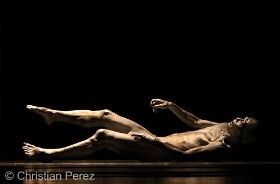

For the general audience, it appears as a type of dance or silent theater which displays extreme visual images created by skinny, white painted dancers. This popular image has spread around the world thanks to the numerous shows given by some of its most famous companies.

Though, butoh aesthetics are much wider and its practice is more than just a new choreographic and visual trend, discovered and developed by the Japanese modern artists.

From the very beginnings, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno (the founders) seem to be in a search for something that can go beyond everything they’ve already seen, including their own performing practices. (Have you ever thought about what would explain the fact that butoh can be executed with or without an audience?)

Remember that Butoh arises within the Japanese society after the Second World War. A mixture of confusion, caused by the industrialization process of their millenary traditional culture, and horror, caused by the bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, cross the social vision of life.

Artists, of course, react in their ways to these circumstances.

Tatsumi Hijikata (1928 – 1986) inaugurates the research with a show entitled “Kinjiki” (Banned colors), in 1959. Based on a novel by the poet Yukio Mishima, the piece presents a young man copulating with a chicken, until he kills it between his legs (I’ve found nowhere if the chicken actually dies or not…).

The audience is outraged and Hijikata is expulsed from the festival were the piece is performed.

But, he continues with his experiments, working over Japanese and French literature (by Yukio Mishima, Lautréamont, Artaud, Genet and the Marquis de Sade) in which he finds grotesque, dark or decadent features. At the same time, he explores the transmutation of the body in other forms like smoke, dust, ghost or animals.

In 1960 he creates “Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs” avec Kazuo Ohno, and then he abandons these sources to search for purely Japanese roots.

Kazuo Ohno (1906 – 2010), who is known to be Hijikata’s close friend and collaborator, becomes famous in Europe with a solo entitled “Tribute to La Argentina” (1977). The piece is motivated by his fascination for Antonia Mercé, a famous Spanish dancer who awakens his desire to dance.

Ohno is then directed by Hijikata, but searches for his own style. The subject of the piece about La Argentina itself shows that his work is oriented in another way (it is told that their sensibility and personality were very different).

With Hijikata directing, Ohno creates two more major works, “My Mother” and “Dead Sea”, performed with his son, Yoshito Ohno. Other works include “Water Lilies”, “Ka Cho Fu Getsu” (Flowers-Birds-Wind-Moon) and “The Road in Heaven, The Road in Earth”.

Here are some of Ohno’s words:

"The best thing someone can say to me is that while watching my performance they began to cry. It is not important to understand what I am doing; perhaps it is better if they don't understand, but just respond to the dance."

"There are an infinity of ways in which you can move from that spot over there to here. But have you figured out those movements in your head, or are we seeing your soul in motion? Even that fleck at the tip of your nail embodies your soul... the essential thing is that your movements, even when you're standing still, embody your soul at all times."

Kazuo Ohno performs during his whole life until he can barely move. People who knew him say that just his presence was like an artistic fact itself.

Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno create the foundations of what Hijikata calls “Ankoku buto” (dance of the darkness).

Their work has been described as the search for a representation of the body that would be free of cultural references and open to all metamorphosis. This presupposes the existence of a natural state of humanity (as opposed to culturally determined) that could be reached and expressed with movement and that would lead to a wide variety of aesthetic results.

Their search for that primary state of humanity, together with their reaction against the contemporary dance scene in Japan (which Hijikata feels is based on imitating the West and the Noh) leads to some of butoh’s common features:

- Search for an individual or collective memory.

-Use of taboo topics: death, eroticism, sex and mobilization of archaic pulsations.

-Extreme or absurd environments.

-Slow hyper-controlled motion.

-Almost nude bodies completely painted in white.

-Upward rolled eyes and contorted face.

-Inward rotated legs and feet.

-Fetal positions.

-Playful and grotesque imagery.

-Performed with or without an audience.

-No set style: “There are as many types of butoh as there are butoh choreographers.” (Hijikata).

-It may be purely conceptual with no movement at all.

- Aesthetical features that go against the western archetypes of perfection and beauty.

- Its technique uses some acquisitions from the traditional Japanese knowledge, like the control of energy, which translates into an insistent rhythm (close to Nô Theater) and strong expressivity.

One of Hijikata’s closest pupils is Ko Murobushi. He is responsible for bringing the pratice to Europe in the 1970s and for creating, in collaboration with Akaji Maro the company Dairakudakan in Tokyo. They cultivate the theater of cruelty and that of Sade’s torments, in a mixture of erotic obsessions and body sufferings.

Sankai Juku

Sankai Juku is one of the most famous butoh groups. Founded in 1975, the company has toured the world under the direction of Ushio Amagatsu.

“...We start from an empty body… we search for an answer to the question of who we are…” says Amagatsu. He also expresses that he is in a search for his own butoh, which seems to have gone away from its initial violence to an extremely slow dance that creates monumental and sumptuous images, full of sophistication and symbolism. His findings have been triumphant worldwide, gaining him not only a huge recognition but the possibility of commercializing his shows successfully.

After Hijikata and Kazuo Ôno, a series of renowned figures from all over the world are found in contemporary dance records. Carlotta Ikeda, with her company Ariadone stands as one of the most recognized women.

Butoh is first rejected in Japan but later, it is greatly received in the western world (especially in Europe in the 70s).

It finally gains a big success in Japan in the 80s, thanks to an artistic trend that is interested in the search for a national identity. Since the 90s, the new generations, strongly determined by the culture of young people, connect Japanese butoh with cultural references from the global society (technologies, design and techno).

Nowadays Butoh is a dance preformed all over the world and mentioned in almost every contemporary dance history record.

Return to Contemporary Dance History

Return to Contemporary Dance Home Page

The handy e-book of CONTEMPORARY DANCE HISTORY:

The Dance Thinker is our occasional E-zine. Fill in the form below to receive it for free and join us.

Read:

"The Dance Thinker"

BACK ISSUES

Post contemporary dance announcements (workshops, auditions, performances, meetings and important news... it is free.)