BALLET HISTORY

Ballet history is commonly divided by historians in chronological periods. Each one of them is recognized because some of the dance features or values prevail over others.

Sometimes we get information about aesthetic or choreographic values but it is common to find all kind of related facts mixed in the ballet history data. That’s why the ballet general history we find in most books is a mixture of biographies, institutional records, different functions that dancing has accomplished for society: political, social, ritual, ornamental…, and other kind of odds and ends…

The following is a rough list of those chronological periods from the XV century (AD) till the present time:

XV - XVI centuries: court dances or pre-classical dance history.

XVI - XVII centuries: court ballet and baroque dance history.

XVIII century: ballet of action.

End of XVIII century - XIX century: romantic ballet history.

Second half of XIX century: classical, academic and/or imperial ballet history.

XX century - present time: modern, neoclassical and/or contemporary ballet history.

If you want to browse through a brief description of each one of the ballet history periods and the names of figures who were or are significant for them, go to our general dance history page. Bellow you’ll find an expanded version of this story.

So…:

XV-XVI centuries: court dances or pre-classical dance history.

This story occurs in the city of Florence (Italy), at the time called the Renaissance (or beginning of the ‘occidental modern era’). Society reacts to important political and cosmological changes. From a ‘dark era’ called the ‘Middle Age’, humans are reborn to a bright period, illuminated by science and knowledge.

Scientific experiments prove that the earth turns around the sun, opposing to what was commonly thought for centuries. People start believing that they are responsible for their lives and that they can improve their existence by their own means (instead of expecting God to do it).

Humans creative capacity stirs up and with the invention of the printing press, knowledge spreads over secular people like never before.

Monarchy is the sociopolitical system. A king has power over everything in his territory, whose administration he delegates to courtiers: princes, dukes, marquises, counts, viscounts, barons, knights…

All these people and their families meet from time to time in the royal palace. Those gatherings are used to celebrate or have big parties, where dancing becomes a privileged way of entertainment and socializing. A new collective ‘rite’ is born: the Court Dance.

By dancing, courtiers show off their manners. Elegance and grace are in vogue, and everybody must learn those ways to move and behave. Therefore a royal dancing master teaches the steps and ways to carry the upper body, arms and hands. The already existing rural popular dances are stylized in the court during this process, according to the aristocracy’s trend.

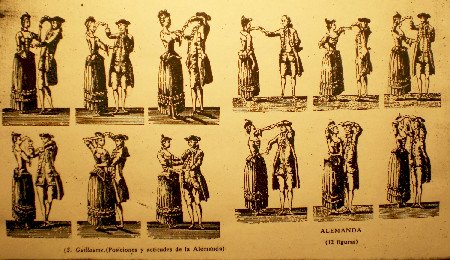

Courtiers dance short choreographic pieces. They correspond to musical fragments that share the same name.

The following is a list of some of those dances:

The Pavane, the Gaillard, the Allemande, the Courante, the Saraband, the Gigue, the Minuet, the Gavotte, the Bourré, the Rigodon, the Passepied, the Chaconne and Pasacaille, the Canarias, the Lour, the Pass mezzo… (The spelling of these names varies a lot. This is an approximate.)

If you want an explanation of each one of those dances try searching for the following book:

Horst, Luis. Formas preclásicas de la danza. Instituto cubano del libro, La Habana, 1971.

That is a Cuban edition, in Spanish, that doesn’t provide other bibliographic data (sorry…), but according to some clues given in the introduction, there must be an English version out there.

Photo taken from the book "Formas preclásicas de la danza". Horst, L., Instituto cubano del libro,1971.

Photo taken from the book "Formas preclásicas de la danza". Horst, L., Instituto cubano del libro,1971.The court dances are really assorted in terms of rhythms, dynamics and nature. Although Italy is recognized as their birth place, all Europe takes part in this social trend. When talking in general terms about them, Luis Horst writes in the introduction of his book:

“It was a mixture of the rich brightness of Italian lifestyle, with the dark religious emotion of Spaniards, the rough vitality of the Netherlands and the pastoral serenity of the English ideals. To this, we must add the troubadours popular art influence with their ‘French love courts’ as well as the danced hymns from the Martin Luther’s German reform.”

XVI –XVII centuries: Court ballet history and baroque dance history.

The custom of dancing in the court turns with time into an arranged act. It is performed to please the king or surprise and welcome foreign visitors.

It is in France where this type of events gains most of their magnificence. They are sponsored by Catalina de Medici, an Italian noble who marries Henry II (second son of the king of France), and moves with her court to that country.

This performances are called ‘ballets’ although they differ a lot from what we understand today as such.

At that time, ballets are performed by the people of the court, sometimes even including the king, and no professional dancers exist. The shows are arranged according to a dramatic story line in which dancing is not necessarily the main component. Animal parades, special effects machinery, poetry, live music, juggling and all kinds of scenic tricks are used.

One of these events is recognized as the first one in ballet history because of its fame and archetypal mode. It is called “The Queen’s Comical Ballet”, performed in 1581 (author: Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx, length: from 5 to 10 hours…!, place: Louvre Palace’s big bourbon hall).

That ballet tells the story of a desperate knight who implores the king to free him of the spell of the sorceress Circe (from the Greek tale “The Odyssey”). After a series of varied scenic entries, the witch is captured and given to him.

Two important features, that will be a common characteristic among all ballets during this period, are manifest in this one.

First, the subject is taken from ancient Greek’s mythology. This is a trend whose roots are found in the early Renaissance, when antique Greek and Roman knowledge is recovered.

Second, the ballet includes the action of comforting and strengthen the image of the king, its power and justice. Ballet history tells us that this is a time in which dancing accomplishes an important political function. Characters and stories are arranged to affirm the monarchic principle and flatter the person of the royal sovereign.

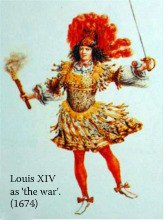

According to ballet history, all European courts copy the Court Ballet model. It’s in the middle of this social environment that the most powerful supporter of dance that has ever existed is born: LOUIS XIV.

As I said above, Louis XIV grows within a society for which dancing is a political tool. As the future king, and part of the aristocracy, he receives ample instruction in science and arts, from which dance is his favorite.

A part from the fact that the young Louis happens to become an exceptional dancer, his social position wins him the task of playing the main roles of the ballets in his court.

Louis XIV in the role of the war

Louis XIV in the role of the warBeside you can see him in the character of ‘the war’ for the Ballet “The wedding of Peleas and Tetis” (1674).

Louis XIV is really passionate about dancing.

In 1661 he reaches the age in which he can rule France alone (without his mother intromission) and starts making political decisions that will greatly determine the following of ballet history.

He founds the Royal Academy of Dance and entrusts its direction to his dancing master: Pierre Beauchamp. At this point, the process of the dancer’s professionalization begins. Academic order and ‘clarity’ start to be preferred than baroque trends or Italian influences.

Other academic activities are sponsored, like the edition of dance books (“Orchésographie” by Thoinot Arbeau in 1588) or the invention of a dance notation system, published in 1700 and named “Feuillet” notation system, according to its inventor’s name.

Other than Louis XIV, three figures are frequently mentioned in ballet history for this period:

Beauchamp (Pierre Beauchamp, 1631 France – 1705 France, choreographer, dancer, royal dance master and director of the royal academy of dance),Lully (Jean-Baptiste Lully, 1633 Italy – 1687 France, composer, violin player and conductor) and Molière (Jean Baptiste Poquelin, 1622 France – 1673 France, playwright and actor.

Lully and Molière work together for the king, but start having aesthetical disagreements in time. While Lully privileges singing and tragedy, Molière prefers acting and comedy.

The genre of the pieces they produce are known in ballet history as Opera-Ballet (or lyric tragedy) and Comedy-Ballet respectively. Dance is for both cases an accompaniment. It accomplishes the function of an ornament that appears between entries or decorates the sung or acted parts.

Around the 1670’s, Luis XIV refuses to continue his performances in ballets. By that time, the shows have long ago gone over the limits of the court. Since 1632, a man called Horace Morel offers ballets to a public that pays for entries at the “Little Louvre” (he could be known as the first business man of the dance industry…). The seeds of ballet as a public event are created. In 1669, the first scenic dance theater is opened by the abbot Perrin.

A little later, in 1673, Lully buys the privilege of the theater and the “Paris Opera” company is created. The members of the aristocracy don´t appear in ballets anymore and dance as a profession is definitively established.

As I mentioned above, dance is not yet an autonomous art, but a complementary element of tragedies or comedies. Considered as an entertaining issue that does not take part of the action, it focuses essentially on the development of technique.

Some selected notorious facts of the time:

• In 1681 the Paris Opera opens its doors to women. Dance, as well as arts, science and knowledge in general were exclusive for men until then…!

• In 1713 the Opera founds its own school, which is entrusted to Pécour, the disciple of the royal dance master Beauchamp.

• In 1725 another important dance book is edited. “Le maitre à danser” (the dance teacher) by Pierre Rameau.

In general terms, ballet history calls this dance ‘baroque’ because it shares features with the general baroque atmosphere in which it is born: ornamental excess, virtuosity and extremely refined manners.

One way to have a close idea of this part of ballet history would be to watch the film “Le Roi Danse” (The King is dancing, released in 2000 by the Belgian filmmaker Gérard Corbiau). There’s not as much dancing as we would like there to be, but it’s a really nice film I recommend you to see.

XVIII century: ballet of action.

As I wrote above, by now dance is very oriented towards technical achievements. Guided by Pécour, skills and style of the Opera dancers replace grace and geometry. This creates the phenomenon of the emergency of great soloists in ballet history.

The following is a list of some of the dancers that are renowned at the time:

Marie Sallé (1702 - Paris 1756), François Prévost (Paris 1680 – 1755), Marie Anne de Cupis de Camargo (Brussels 1710 – Paris 1770), Gasparo Angiolini (Florence 1731 – Milan 1803), Jean Bercher ‘Dauberval’ (Montpellier 1742 – Tours 1806), Maximilien Gardel ‘the Old’ (Mannheim 1741 – Paris 1787), Pierre Gardel ‘ the Young’ (Nancy 1758 – Paris 1840), Marie – Madeleine Guimard (Paris 1743 – 1816), Gaétan Vestris (Florence 1729 – Paris 1808), Auguste Vestris (Paris 1760 – 1842)…

Two female dancers are frequently mentioned by ballet history books. They are remembered because they introduce daring innovations in dancing costumes and are recognized as the expression of two main dance features: technical virtuosity and lyricism.

Marie Camargo is the bodily skilled dancer. She is the pupil of Mmlle. Prévost and makes her first appearance at the Paris Opera in 1726. She shortens the skirt above the ankles, invents the ‘covering pants’ (ancestors of the current tights…?) and uses dancing shoes without heels.

Marie Sallé on the other hand is the lyrical, expressive dancer. Coming from the same teacher, she makes her career at the Opera between 1727 and 1740. She is known as being the first dancer who abandons the usual wig and crinoline dress, to use a Greek style muslin tunic.

But, what gives this period its historical name is the aesthetic revolution accomplished by Jean Georges Noverre (France 29 April 1727 - 1810).

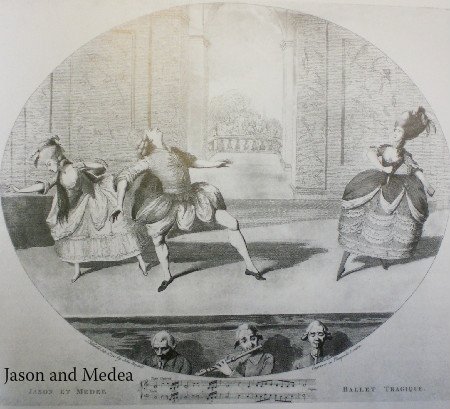

Noverre's Jason and Medea

Noverre's Jason and MedeaYou might have heard of him, because nowadays the international day of dance honors and celebrates his birthday.

He is so important for us, because he promulgates the idea of dance as an autonomous art. Ever since, dance is understood in ballet history as a major art in itself and steps forward from being an ornament to be a subject of artistic knowledge.

Noverre, other than creating dance pieces, writes his ideas in the form of letters or articles. These are some of the texts we have access to (theses titles are in French but the manuscripts have been translated into several languages):

• "Lettres sur la danse et les ballets »

• "Observations sur la construction d’une nouvelle salle de l’Opéra"

• "Deux lettres de M. Noverre à Voltaire"

• "Lettres à un artiste sur les fêtes publiques"

• "Théorie et pratique de la danse en général, de la composition des ballets, de la musique, du costume, et des décorations qui leur sont propres".

I recommend you the first one of the books listed above. However here’s a list of some of his most important ideas, in case you want to go brief:

• Dance must carry a dramatic action. Without overdoing in its divertimentos, it must describe passions, manners and traditions of people.

• The choreographer must interpret the natural and truthful way of things; he must offer a logic story, like in a theater play, with an exposition, conflict, climax and ending.

• Dance must be natural and expressive, more than technical and virtuous.

• The “dance of action” must move the audience by the means of an expressive pantomime, inspired in the ways of theatrical plays.

• The dancer must have a broad general culture that includes the study of poetry, history, painting, music and anatomy.

• Dance should not be hieratical. Masks should not be used, because they dissimulate the soul’s affections. Realistic and better adapted to dance costumes must be used.

A part from being an important thinker of the ballet history records, Noverre produces a lot of dance pieces all over Europe. Here’s the name of some of his most important Ballets:

Les Fêtes chinoises (Paris 1754), La Fontaine de jouvence (Paris 1754), La Toilette de Vénus (Lyon 1757), L'Impromptu du sentiment (Lyon 1758), La Mort d'Ajax (Lyon 1758), Alceste (Stuttgart 1761 - Vienna 1767), La Mort d'Hercule (Stuttgart 1762), Psyché et l'Amour (Stuttgart 1762), Jason et Médée (Stuttgart 1763 - Vienna 1767 - Paris 1776 et 1780 - Londres 1781), Hypermnestre (Stuttgart 1764), Diane et Endymion (Vienna 1770), Le Jugement de Pâris (Vienna 1771), Roger et Bradamante (Vienna 1771)…

Towards the end of this period, another choreographer creates a piece that announces the beginning of a new political and aesthetic period.

“La fille mal gardée” (1789 - Bordeaux), by J. Dauberval is a ballet in which the main characters are country people. Ballet reflects the incipient falling of the monarchic system and starts shaping in response to a new society.

End of XVIII century – XIX century: romantic ballet history.

"Giselle", The emblematic piece of the romantic period.

"Giselle", The emblematic piece of the romantic period.Romanticism is a word used in art history to name a cultural (and aesthetical…) trend that spreads in Europe during this period. For society, this is a time of lost illusions, unease and disappointment with the failing of the French revolution and what it represents.

Concerning arts, Romanticism has many variations according to local contexts so I’ll concentrate in what is known to be some of the main features of Romantic Ballet:

• Two acts: a first one that is about the real world and a second one that is about the unreal.

• Expression of the soul.

• Made for the lightness of the ballerina, which represents ethereal beings.

• Major figures are women. The ballet is created for the female ‘stars’.

• The use of pointes is established (since 1813). The ballerina reaches the highest level in space.

• Change from the ‘traditional’ ancient Greek-Roman inspiration sources to the use of mythologies from other European cultures: fantastic world of L. Byron, ghostly middle-age atmosphere of W. Scott, misty magic of German poetry, characters of fairies, spirits, goblins…

• Poetry, lightness, grace, softness, miraculous effects…

• Importance of the expression and lyricism of the dancer.

• Impossible love stories. Love between mortals and spirits.

• White chiffon skirts.

This is the time when some of the current popular archetypes of ballet are born: sentimentalism, free love, extreme idealism against a miserable reality, love for nature as the truthful against civilization, cult of the individual person, exalting of sensibility over reason, heart and imagination that rule…

Four dancers are very famous for this period in ballet history:

• Maria Taglioni (Stockholm 1804)

• Fanny Elssler (Vienna 1810)

• Carlotta Grissi (Italy 1819)

• Fanny Cerrito (Italy 1817)

And off course, these two ballets (I bet you’ve heard of them…):

“The Sylph” (1832): choreography by Filipo Taglioni, script by M. Nourrit, main dancer Maria Taglioni.

“Giselle” (1841): choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, script by Théofile Gautier and Vernoy de Saint Georges, music by Adolphe Adam, scenography by M. Cicéri, main dancer Carlotta Grissi .

Luckily, these pieces are still alive and are performed by different companies around the world. So I leave it up to you to go and see the current versions.

Complete videos (or online fragments) are also easily available and I promise that I’ll be providing those for you at our site soon. Just remember that contemporary versions may be slightly or very different from the original versions. So, pay attention to the producer’s comments.

Second half of XIX century: classical dance history, academic ballet history and/or imperial ballet history.

Odette and Odile, the two antagonic characters of "Swan Lake", the archetype of classical ballet.

Odette and Odile, the two antagonic characters of "Swan Lake", the archetype of classical ballet.Till here, our ballet story happens in France. Now is the time for a new removal, as the Russian empire starts to assign enormous budgets for ballet shows and its practice.

In 1801, Charles L. Didelot founds the ballet school of Saint Petersburg. Since that moment, French and Italian dance masters like Alexis Blache, J. Perrot, Arthur Saint-Léon (in 1859) or Enrico Cecchetti (in 1887) are invited to work there.

One of the most remembered of these artists is Enrico Cecchetti (Italy 1850 – Italy 1928). He was a dancer but is most recognized for his teaching skills and the development of his own technique. Since the 1890s he works for the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg as a teacher, having figures like Anna Pavlova, Leonid Massine or Vaslav Nijinski as pupils.

But, the main figure of this period is the French Marius Petipa.

By the middle of the century, French ballet is declining. When in 1847, Petipa is invited by the Russian Ballet to work for them, he moves to Saint Petersburg where he’ll make a career of sixty years.

Having the Mariinsky Theater as home, he rules over a company of 250 dancers, 80 students, more than 100 musicians and composers like L. Minkus, C.Pugni, R. Drigo.

Ballet history recognize the pieces of the time for including the choreographic vocabulary from the French school and the technical achievements of the Italians. Ballet reaches an academic peek that displays extreme technical virtuosity.

Petipa makes use of that strength, integrating it with theatrical sense, fairy tales, mime and character dances (Spanish, Chinese, Hungarian, Indian, Scottish, Russian...).

He also creates variations for the ‘étoiles’ (stars in French) and participates on the establishment of the ‘Pas de deux’ form (duo, male part, female part, coda).

In 1881, P.I. Tchaikovsky starts working for Petipa as a composer. This alliance creates some of the most famous dancing pieces in occidental ballet history: “Swan lake” (1895), “The Nutcracker” (1892) and “The Sleeping beauty” (1890).

Although that trio might be the most recognized of Petipa’s creations, he is the author of over 50 Ballets: “Don Quixote”, “Cinderella”, “The Corsair”, “Raymonda”, “The Four Seasons”, “Carmen and the Bullfighter”, “Paquita”, “The Bayader”, “The Grand pas classique”… just to name some of them.

The end of the XIX century in Russia is a golden age for ballet. But, like everything in culture, it evolves to follow new or better adapted to society paths. Dancers that were educated during this period will lead their knowledge to new frontiers. M. Fokine, V.Nijinsky, B. Nijinska, T.Karsavina and A. Pavlova, to name some, will carry the Russian triumph of academic ballet to the European trends of modern art.

XX century – present time: modern ballet history, neoclassical ballet history and/or contemporary ballet history.

Ana Pavlona dancing "The Dying Swan" by M. Fokine.

Ana Pavlona dancing "The Dying Swan" by M. Fokine.The XX century is a time when Russian ballet returns to its European home. From the hand of an art producer called Serge Diaghilev (1872 – 1929), classical dance comes back with its established repertory and innovative offerings.

Diaghilev is not an artist, although he appreciates art and has visual and musical education. As part of the elite intellectual circles of San Petersburg, he has the idea of educating the popular Russian audience into the knowledge of arts.

Following hat idea, he elaborates a plan to divulgate Russian arts (painting, music, theater, and dance) in his own country and then opens his project to a bigger goal: Europe. This is how, after his success with some visual exhibitions, he decides to bring ballet to Paris.

In 1909, he offers a first show with a selected group of dancers from the Imperial Ballet. The show is presented at the Châtelet Theater and gives birth to what will be called in ballet history the “Diaghilev’s Russian Ballet Company”.

The Parisian liking of the time for ‘exotic’ shapes gives them a warm welcome. They create new pieces like “Pavillon d’Armide”, “L’oiseau de feu” or the “Polovtsian Dances”.

Diaghilev is not a choreographer. Instead, he entrusts the task to figures like M. Fokine, V. Nijinsky, Léonide Massine, B. Nijinska or G. Balanchine who are also dancers of the company beside A. Pavlova, T. Karsavina or S. Lifar.

Together they develop the idea of creating a “total piece of art”: a product in which all aesthetic languages would be coherent and would converge with a same sense. That’s why they integrate artists from other disciplines in their productions.

These are some of the figures that collaborated in the project:

Visual arts: León Bakst, Alexander Benois, Nicolas Roerich, P. Picasso, A. Derain, H. Matisse, M. Laurencin, G. Braque, H. Laurens, C. Chanel, M. Utrillo, N. Gavo and A. Pevsner, G. Rouault…

Music: I. Stravinsky (who might be the most important of his music collaborators, author of the famous “L'oiseau de feu” or “Fire Bird”), M. Ravel, E. Satie, F. Poulenc, G. Auric, D. Milhaud, H. Sauguet, S. Prokofiev…

Drama: J. Cocteau…

The “Russian Ballets Company” lives until the dead of Diaghilev. In 1929, after 20 years of artistic production, the group dissolves leaving a choreographic heritage that influences the work of many dance companies till today.

"Les Noces" by Bronislava Nijinska.

"Les Noces" by Bronislava Nijinska.Pieces like “The rite of Sprig” and “L’après midi d’un faune” (“The afternoon of a faun”) by Nijinsky, or “Noces” (“The Wedding”) by Nijinska, are still reinterpreted or quoted by recognized contemporary choreographers. They carry some important seeds of the shape of ballet during the rest of the XX century and forward.

After Diaghilev’s time, different countries in the world have prepared the conditions for the maintenance of stable and professional ballet companies.

Dancers and choreographers mix their choreographic legacy with modern and contemporary art values, creating a really wide variety of creative issues and styles.

Powerful ballet companies grow and spread all over the world, led by figures like Maria Rambert and Ninette de Valois (England), George Balanchine (U.S.A.), John Cranko (South Africa), Rudolf Noureev (Russia), Maurice Béjart (France), Kenneth Mac Millan (England), Robert Joffrey (U.S.A.), Jirí Kylián (Netherlands), William Forsythe (U.S.A.), Mats Ek (Sweden) , Nacho Duato (Spain), Jean Cristophe Maillot (Monaco)…

As the historical data is much broader for this period, I’ll finish the ballet history tale here. You can find a list of some of the ballet history books used for this summary at the end of my general dance history page.

Written and published by Maria Naranjo, 2010.

Remember that you can write to me through the form at our page for dance questions. I’ll do my best to provide or add the content of your preference to our site. Just come back to contemporary-dance.org and find it!

Related readings:

Ballet cultural values and ideas

Do you need to take ballet to do contemporary?

(In Spanish) Definición de Danzas de Carácter

Return from Ballet History to Dance History

Return from Ballet History to Contemporary Dance Home Page

The handy e-book of CONTEMPORARY DANCE HISTORY:

The Dance Thinker is our occasional E-zine. Fill in the form below to receive it for free and join us.

Read:

"The Dance Thinker"

BACK ISSUES

Post contemporary dance announcements (workshops, auditions, performances, meetings and important news... it is free.)